Jelenlegi hely

Anatol Josepho. From Stickyback Photography to the Invention of the Photomaton Photobooth

Stickyback Pictures and Photomaton Photos made in Budapest that can be linked to Anatol Josepho and his family

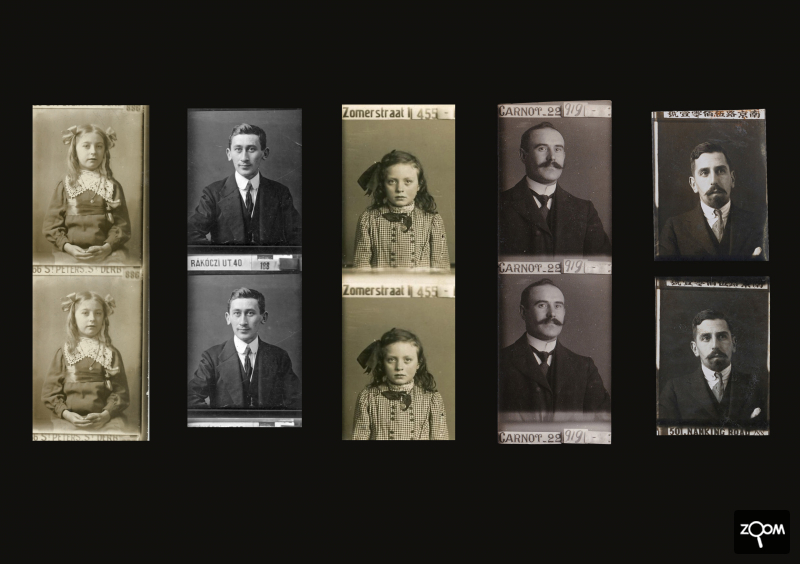

On the left side: Stickyback Pictures made in the 1910s, in the studio “Enyves hát” of 40 Rákóczi Street; on the right side: a series of Photomaton Photos made in 1934 in the “Corvin” department store (on the opposite side of Rákóczi Street). Credit: Collection of János Mátyás Balogh

Several similarities can be discovered between the external features of these two successive photographic styles. In both cases, the client received a cheap and originally uncut strip of untouched portraits or bust-photos. One below the other, they were approximately the size of today’s passport photos.

Appearing at the turn of the century, Stickyback Photography flourished in the 1910s. Its method combined already available photographic tools and procedures into a new business model.

The Photomaton Photobooth, on the other hand, was a patented invention. Although coin-operated photo automatons had been developed much earlier, it was ultimately Josepho’s machinery in the late 1920s that helped to spread the photobooth worldwide as it still exists today.

The Stickyback Photography

Clients visiting simple Stickyback stores were given a single shot with minimal photographic instructions and artificial light, from which they were then able to take 12 copies the next day. The photo was taken usually with a so-called “multiplying/repeating back” camera, which was able to take several shots of successive clients on a single larger glass plate side by side (and one below the other). Clients were given little time. The photos were also identified by a serial number placed on a bar, usually behind, less often in front of the client about to be photographed. Based on this serial number, one could receive their completed pictures.

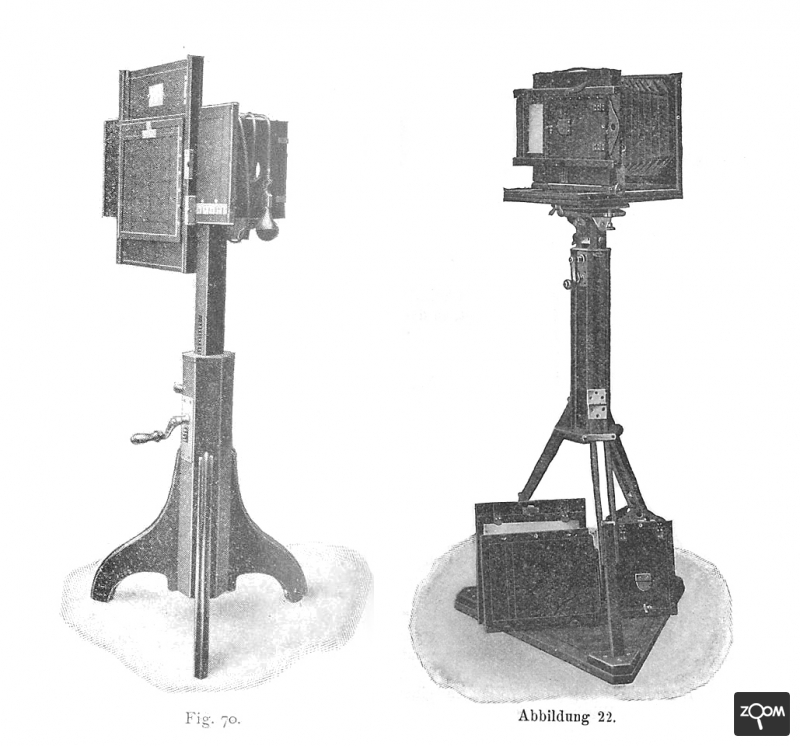

Cameras with repeating/multiplying back manufactured by Ernemann Werke AG. (Görlitz, Germany), recommended for Stickyback Photography.

Source: Josef Maria Eder (Hrsg.): Jahrbuch für Photographie und Reproduktionstechnik für das Jahr 1913. Halle a. S., 1913. p. 252. and Kögel P.R.: Die Photographie: historische Dokumente nebst den Grundzügen der Reproduktionsverfahren. Leipzig, 1914. page 31.

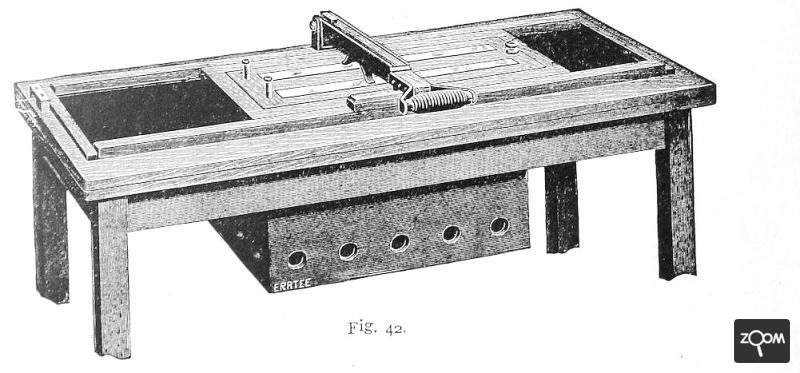

Contact copier for bromide strips manufactured by Romain Talbot (Berlin, Germany), recommended for Stickyback Photography.

Source: Josef Maria Eder (Hrsg.): Jahrbuch für Photographie und Reproduktionstechnik für das Jahr 1913. Halle a. S., 1913. page 213.

From each line of the developed glass plate negative, 12 contact copies were printed on a wider strip of bromide paper with a fast contact printing device. These stripes were then cut into strips along their length so that 12 pictures were placed on each paper strip. The most common size was 3x4 cm and its “multi-person” double format (6x4 cm).

It is worth noting that the multiple negative procedure was used in the United States in the late 19th century, including by the photographic style also produced small busts, known as the “penny pictures”. In this case, however, a series of exposures were taken, then a contact copy was made of the glass plate. Finally, the customer would usually receive a paper strip with various pictures of them (for the topic of the “penny pictures” see Patrick Feaster's excellent article).

Originally, Stickyback photos in the British Isles, Hungary and Austria had an adhesive coating on the back, hence its name. This way, the photos could be immediately moistened and then stuck on a surface (album, postcard, etc.), since the photographer did not mount the images. (In many countries, in addition to small busts, other typical products of Stickyback stores were photos, usually full-length pictures printed on postcards.)

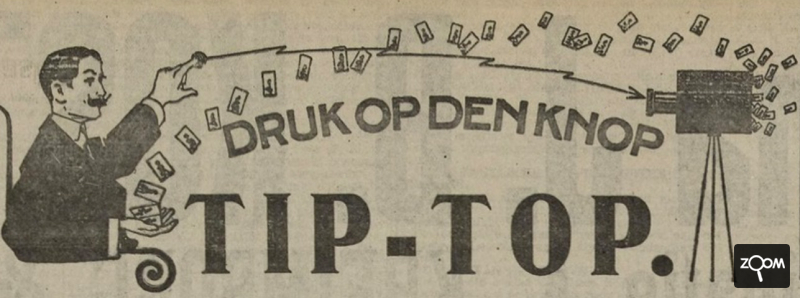

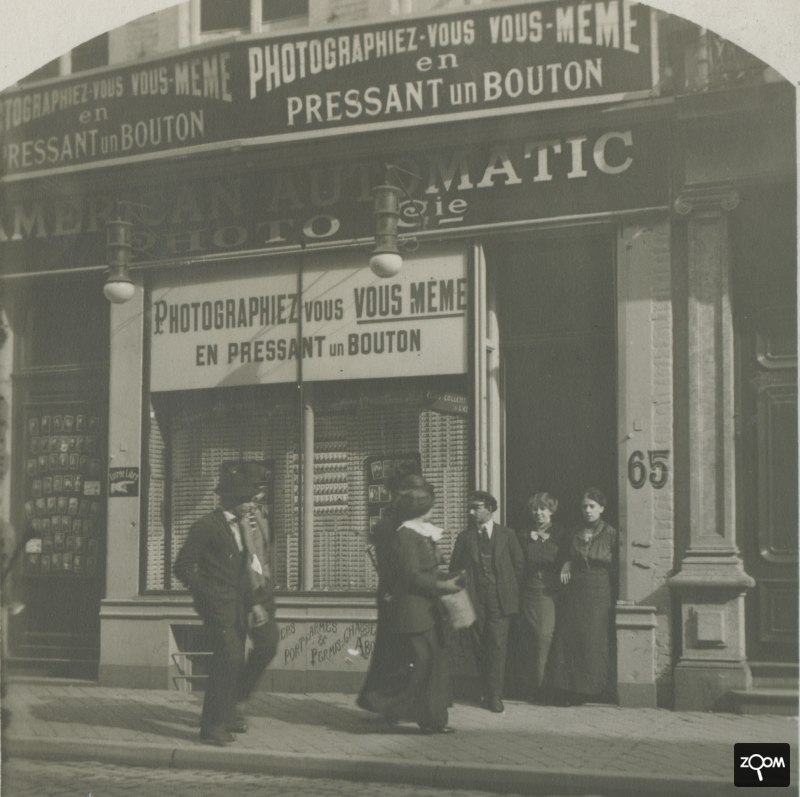

In some countries, in the field of Stickyback Photography, there were companies as well as networks of companies that described their photographic services as “automatic”. Clients were given the illusion of automatism by pressing a button to snap the photo themselves, a process that was not a novelty in the history of photography. This way, customers could take their own self-portrait.

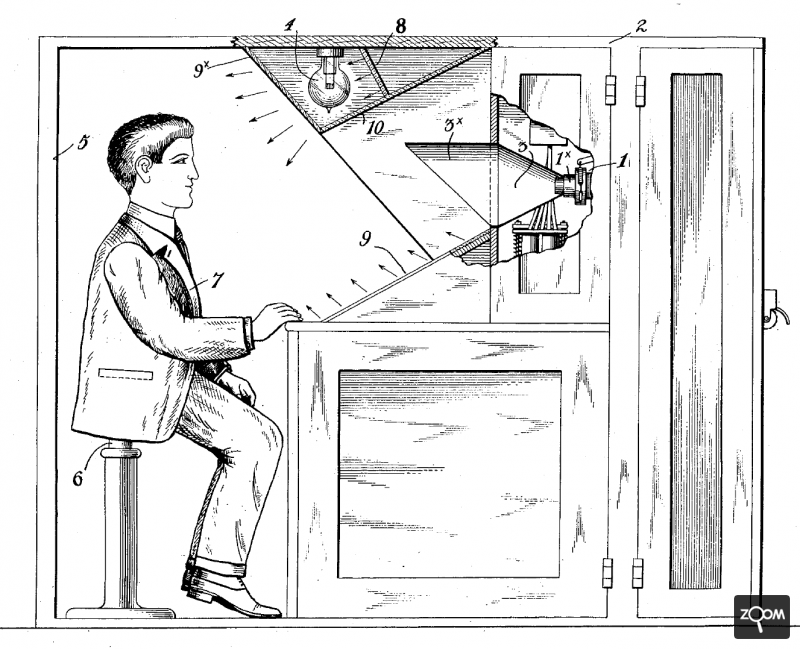

An idealized representation of an “automatic” Dutch Stickyback Photo Studio’s operation (the camera did not actually “spit out” the finished images)

Source: Schager Courant, 12 juni 1915. page 4.

The spread of Stickyback Photography

The global phenomenon of photographic portraiture, once known by different names but defined by the author uniformly as “Stickyback Photography”, first appeared as “Stickyback” in 1901, on the Isle of Man, in Great Britain. This year, the following letter was sent to the editor of the most prominent British photographic magazine: “Will you be so kind as to reply to the following inquiries: The name of the firm that sell the camera used for what are termed ‘Stickybacks’, which have been the rage in Douglas, I.o.M.” (British Journal of Photography, 11. October 1901. 656.). However, the term “Stickyback” was unknown to the editor.

Although the Stickyback style had been already spreading widely across the British Isles for a decade (for British Stickybacks, see Les Waters’ excellent website), however, its 1911 international expansion exploded in Hungary.

Yakov Olykovsky (Mariinsk, Siberia, Russia, 1884 – Budapest, 1924) arrived in Budapest, the capital of Hungary, in February 1911 to introduce Stickyback Photography. By doing so, Olykovsky (in Hungary, he called himself Olychovszky Jankely, later Olychovszky Juhász Jankely/János) involuntarily launched the intercontinental success of Stickyback Photography. The details of the procedure and the business model were shared by his originally fur trader cousin, Abram Dudkin, who had previously settled in England and had a Stickyback Studio in Brighton (for Dudkin’s Studio see David Simkin’s website.

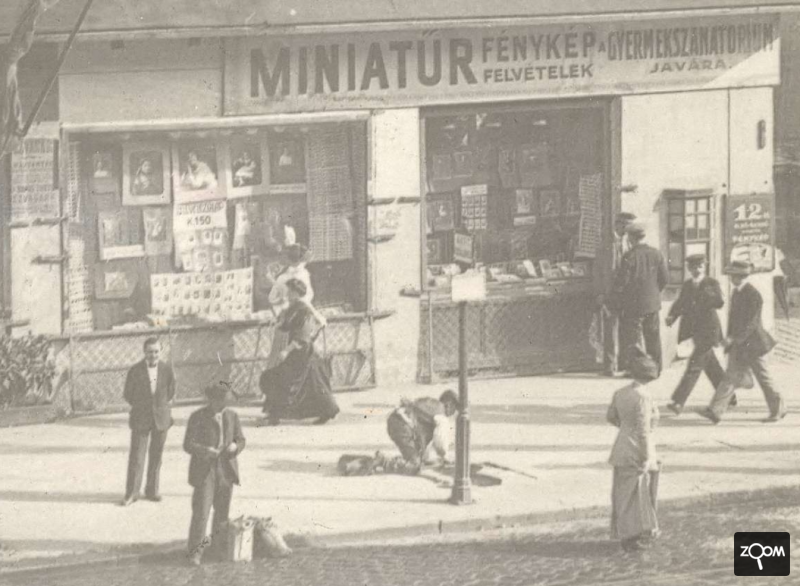

Olykovsky opened his studio in the spring of 1911 (no later than the first half of April), at 40 Rákóczi Street, in a very busy part of downtown Budapest. He gave his shop the name “Enyves hát”, a direct translation of the word ‘sticky back’ in Hungarian. His business immediately became a huge success. People crowded to take pictures of themselves. Within a few weeks, Budapest became full of photographic studios with a similar name and similar products. Many saw a lucrative business opportunity since Stickyback photography was relatively easy and inexpensive to copy and master, while it promised enormous profits. However, success was not guaranteed, and most of the new entrepreneurs failed soon.

Budapest, Rákóczi út 40. [“Enyves hát”] (Credit: Collection of Zsuzsa Farkas); Budapest, József körút 9. [“Enyvezett hát”] (Credit: Collection of Fővárosi Szabó Ervin Könyvtár, Budapest Gyűjtemény/Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library, Budapest Collection); Budapest, Király utca 69. [“Enyves fénykép”] (Credit: Collection of Károly Kincses); Budapest, Károly körút 3. (Credit: Collection of Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum/Hungarian National Museum)

Budapest, Teréz körút 29. (Credit: Collection of Petőfi Irodalmi Múzeum/Petőfi Literary Museum); Budapest, Rákóczi út 51. (Credit: Collection of Zsuzsa Farkas); Budapest, Rákóczi út 1. (Credit: Collection of Fővárosi Szabó Ervin Könyvtár, Budapest Gyűjtemény/Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library, Budapest Collection); Budapest, Fehérvári út 27. (Credit: Collection of Zsuzsa Farkas)

Budapest, Király utca 21. (Credit: Collection of Károly Kincses); Budapest, Váczi körút 14. (Credit: Collection of Károly Kincses); Budapest, Rákóczi út 1. (Credit: Collection of Károly Kincses); Budapest, Andrássy út 15. (Credit: Collection of Károly Kincses)

Budapest, Üllői út 42. (Credit: Collection of Károly Kincses); Budapest, István út 28. (Credit: Collection of Károly Kincses); Budapest, Margit körút 5.b. (Credit: Collection of Károly Kincses); Budapest, Üllői út 97. (Credit: fortepan / Endre Baráth)

The Stickyback craze spread soon across Hungary. It reached provincial towns already in the spring/summer of 1911.

Gyula, in front of Hotel Komló (Collection of Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum/Hungarian National Museum); Andrássy utca 9., Hódmezővásárhely (Collection of János Mátyás Balogh); Széchenyi utca 9., Miskolc (Collection of János Mátyás Balogh); unknown location (Collection of János Mátyás Balogh)

Sopron (Credit: Collection of Petőfi Irodalmi Múzeum); Nádor utca 18., Székesfehérvár (Credit: Collection of Miklós Grégász); Erzsébet út 2., Kaposvár (Cedit: Collection of Károly Kincses); Király utca 17., Pécs (Credit: Collection of Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár)

Deák Ferenc utca 1., Marosvásárhely (Credit: Collection of Károly Kincses); Piacz utca 58., Debrecen (Credit: Collection of Károly Kincses); unknown location (Credit: Collection of Károly Kincses); Fő tér, Zalaegerszeg (Credit: Collection of Károly Kincses)

Baross utca 20., Győr (Credit: Collection of Károly Kincses); unknown location (Credit: Collection of Károly Kincses); unknown location (Collection of Zsuzsa Farkas); unknown location (Credit: Collection of János Mátyás Balogh)

unknown location (Credit: Collection of Károly Kincses); unknown location (Credit: Collection of Károly Kincses); unknown location (Credit: fortepan / Imre Del Medico)

In the summer of 1911, some Hungarian entrepreneurs brought the new photographic style to the nearby Austrian capital. Within a short time, dozens of Stickyback stores started to operate in Vienna too. In Austria, this new photography was most often referred to as “Leimrücken” or “Kleberücken”, the German translation of “enyveshát”/Stickyback.

From here, already in 1911, Stickyback Photography reached Germany.

In early 1912, it also appeared in The Netherlands (known as “tip-top photography”) and Belgium. It seems that Stickybacks have been taken in France as early as the summer of 1911.

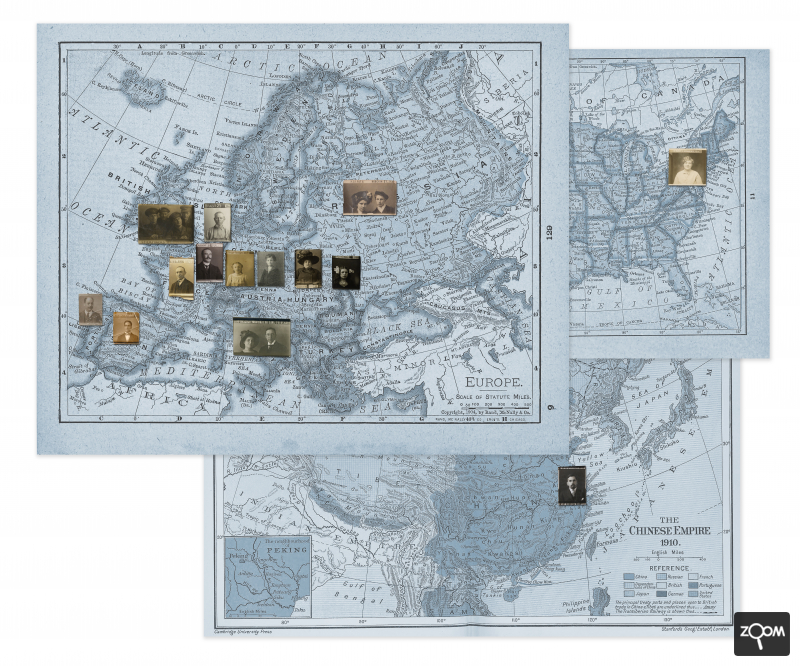

After 1911, during the 1910s, this portraiture method spread not only in Europe (e.g., Italy, Switzerland, Portugal, Spain, Russia, Poland, Sweden etc.) but also made it to the United States and China.

Examples from Portugal, Spain, United Kingdom, France, The Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Austria, Hungary, today’s Poland, Russia, Italy, China and United States from the 1910s

Armazéns do Chiado, Lissabon, Portugal; Montera 42, Madrid, Spain (Credit: Collection of Eduardo Martínez); 74 Above Bar, Southampton, United Kingdom (Credit: Collection of State Library of South Australia); 26 Rue de Rivoli, Paris, France (Credit: Collection of Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár/National Archives of Hungary); Brugstraat 25, Groningen, The Netherlands (Credit: Collection of Groninger Archieven); Carnotstraat 22, Antwerp, Belgium (Credit: Collection of Peter Eyckerman); Krüger Passage, Dortmund, Germany; Vienna, Austria (Source: Photographische Korrespondenz, Oktober, 1911. page 555.); Rákóczi út 40., Budapest, Hungary (Credit: Collection of Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum/Hungarian National Museum); Piotrkowska 100, Lodz, today’s Poland; Nevsky Prospekt 27., Saint Petersburg, Russia (Credit: Collection of L.B. Ivanova); Bacino Orseolo, Venice, Italy (Credit: Collection of Petőfi Irodalmi Múzeum/Petőfi Literary Museum); 501 Nanking Road, Shanghai, China (Collection of Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár/National Archives of Hungary); 70 Market Street, Newark, New Jersey, USA (Credit: Collection of Patrick Feaster)

66 St. Peters Street, Derby, United Kingdom (Credit: pastglances.blogspot.com); Rákóczi út 40., Budapest, Hungary (Credit: fortepan); Zomerstraat 1, Tilburg, The Netherlands (Credit: Regionaal Archief Tilburg); Carnotstraat 22, Antwerp, Belgium (Credit: Collection of Peter Eyckerman); 501 Nanking Road, Shanghai, China (Credit: Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár/National Archives of Hungary)

Traditional photographers, in several places, looked down on and legally obstructed the widely popular Stickyback Photography. The model gradually disappeared in most countries by the early 1920s. Both the process and its worldwide proliferation were forgotten for a long time.

Budapest, 1 Rákóczi Street (1911/1913), Credit: Fővárosi Szabó Ervin Könyvtár, Budapest Gyűjtemény/Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library, Budapest Collection

Liége, 65 Rue de la Cathédral (1912/1913), Credit: Collection of Peter Eyckerman

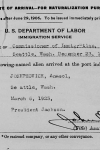

Anatol Josepho and the Photomaton

Several of Yakov Olykovsky’s family lived in Budapest. Grigory Vishniak, spelled as Gregory Wishniak in the US (Tobolsk, Siberia, Russia, 1873 – Los Angeles, 1958), was the husband of one of Olykovsky’s maternal aunts. In 1912, he (and his wife, Hasya) had certainly been in the Hungarian capital. Perhaps he had even taken over the store Enyves hát’s management when in the summer, his nephew, already Hungarian citizen Yakov Olykovsky traveled to New York via Hamburg.

In New York, the nephew of Grigory Vishniak, a certain Abram Iosifovich, joined Olykovsky in November 1912.

Abram Iosifovich – the future Anatol Josepho – was born in Tomsk, Tsarist Russia, on March 31, 1894, to the Siberian Jewish family of Mordecai/Mark Iosifovich and Esther Vishniak.

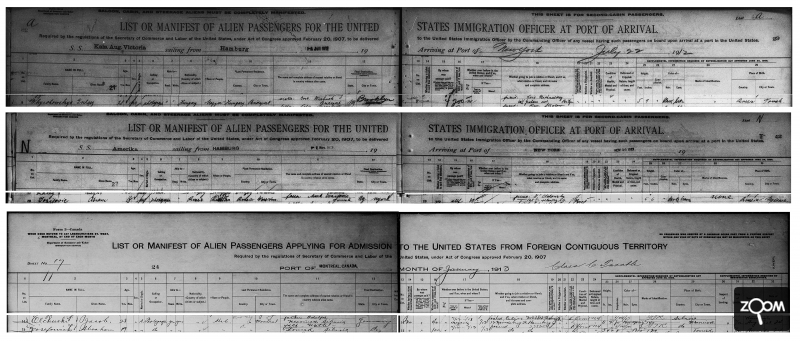

Almost nothing is certain about his youth. Biographical writings published in American journals after 1927 (e.g. Photo-Era Magazine, McClure’s Magazine, American Hebrew and Jewish Tribune, Modern Mechanics) can only be trusted with strong criticism, as they contain several certainly erroneous elements. Abandoning his technical studies, Iosifovich supposedly left Siberia around 1910 at the age of 16. It is certain that he arrived in New York in 1912 from the German port city of Hamburg. US Passenger Arrival Record states that his last permanent residence was Warsaw, a Polish city then part of tsarist Russia.

Finally, the two young photographers, Olykovsky and Iosifovich returned to Europe, Hamburg together in January 1913 after a very short trip to Montreal, Canada.

Source: “New York Passenger Arrival Lists (Ellis Island), 1892-1924” and “Vermont, St. Albans Canadian Border Crossings, 1895-1954” via FamilySearch

In the spring of 1913, Yakov Olykovsky was in Budapest again. His nephew, Abram Iosifovich followed him there at the latest by the end of the same year. We know this, because he was registered in the Hungarian capital as “Josifowitsch Ábrahám”.

Naum Sviatochevsky (Mariinsk, Siberia, Russia, 1896 – Santa Monica, USA, 1992) was a cousin of Olykovsky. Sometime in early 1914, he arrived in Budapest to work as a photographer in his cousin’s studio.

The young Abram Iosifovich worked in the laboratory of the “Enyves hát” store in Budapest, already spending his spare time designing a photo automaton. In May 1918, he or his agent filed his first patent application here, in the Hungarian capital.

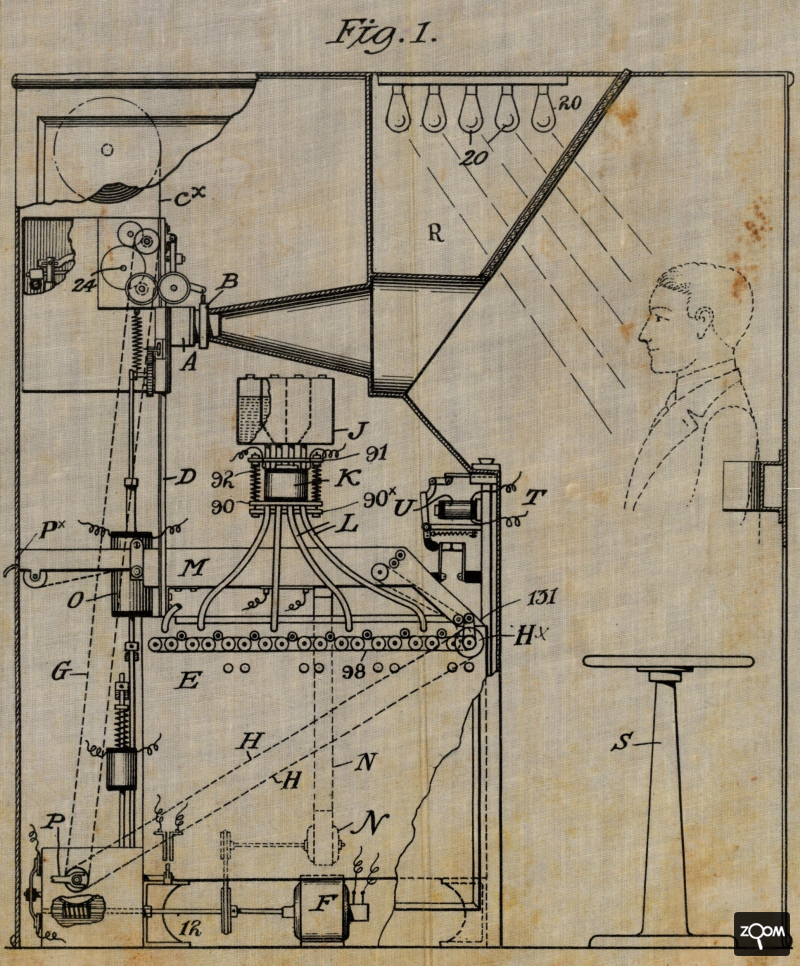

The first known patent of Anatol Josepho (as “Josefovics Ábrahám”)

Hungarian Patent No. 74087. “Combined dark chamber with developing and fixing device” Source: Szellemi Tulajdon Nemzeti Hivatala/Hungarian Intellectual Property Office

Abram Iosifovich left Budapest at the end of the First World War under adventurous conditions, arriving in Shanghai via Siberia and Manchuria. After a five-year stay in Manchuria and China, he traveled to Seattle in March 1923. By this time, for reasons unknown, he was already using the name “Anatol” and claimed to be born in Latvia. The same year he moved to New York, where he shortened his surname to “Josepho”, just like his Latvian-born cousins, who had been living in New York for decades. He also adopted the name “Marco”, a reference to his father’s first name (Mordecai/Mark).

Source: “Washington, Seattle, Passenger Lists, 1890-1957” via FamilySearch

Anatol Josepho’s documentation of naturalization (1924–1928)

Source: “New York, Southern District, U.S District Court Naturalization Records, 1824-1946” via FamilySearch

The first photo automatons, which performed all phases of shooting and developing, appeared decades before the Photomaton. From 1888, designs and patents for such machines were popped up both in America and Europe; however, most of them did not even become prototypes. The first photo automaton that became successful in the long run was Anatol Josepho’s Photomaton. Following its appearance, similar structures from other companies were created, making the automatic photobooth a real cultic place in the “Western world”.

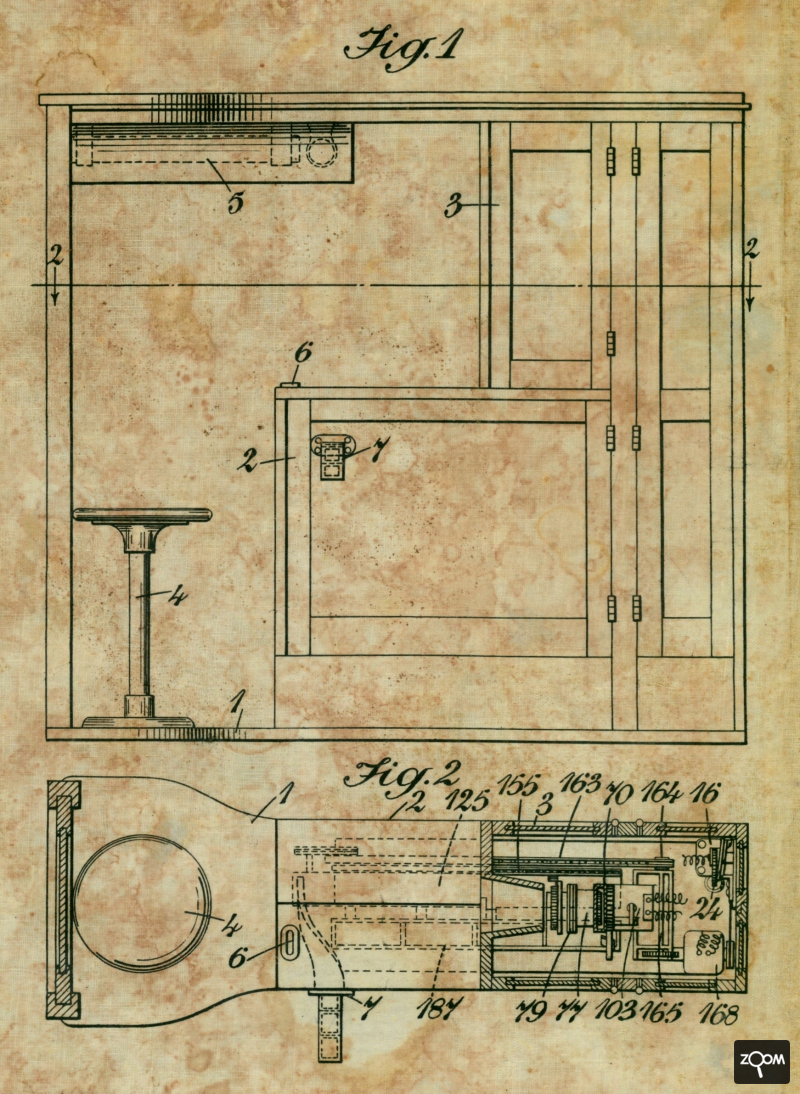

Josepho’s invention was a coin-operated booth that took eight (or six) consecutive shots in twenty seconds of a person sitting in front of the camera. The developing, washing and drying of the photographs (3.5 × 5 cm sized busts) took eight minutes. Using a direct positive method, that is, they were taken directly on a paper roll coated with a photosensitive material, they were played one below the other, on an uncut strip of paper. Compared to the photo automatons that were widespread in previous decades but unsuccessful in the long run, the main innovation of Josepho’s machine was that instead of a single shot, it took a series of excellent quality exposures.

Between September 1923 and March 1925, Anatol Josepho filed his patent applications for a photobooth in the United States. These four patents (Patent Numbers: 1.671.644 – Automatic Camera for Taking Timed Sequences of Portraits; 1.631.593 – Photographic Apparatus; 1.656.522 – Developing Apparatus for Photographic Film Strips; 1.658.167 – Electric Coin-Control Mechanism) were all granted the rights conferred on Photomaton Inc. The company was formed in New York on January 8, 1925. It was created to provide an official framework for those wanting to invest in Josepho’s invention, including his relatives, such as his uncle Gregory Vishniak, his cousin John Josepho and the latter’s father in-in-law, Harry Friedman.

Josepho began the international protection of his invention as early as 1923 (in Great Britain).

Josepho’s British photobooth patent presented on December 31, 1923 (GB Patent Number: 231.926) with the drawings of this patent from the collection of the National Archives of Hungary

Reference: Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár/National Archives of Hungary, MNL OL K 603-P-6639

In the summer and autumn of 1925, Anatol Josepho filed patent applications in many countries worldwide, including Hungary.

Reference: Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár/National Archives of Hungary, MNL OL K 603-P-6639.

Source: Espacenet.com

Reference: Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár/National Archives of Hungary, MNL OL K 603–J–2531.

Source: The Illustrated London News, February 25, 1928.

By July 1925, after four years of planning and a year and a half of construction, the first working prototype was completed in New York. During 1925 and 1926, Josepho and his partners opened a few smaller studios in the city.

The first “real” Photomaton studio with five improved machines opened in September 1926 in New York at 1659 Broadway. The new photography genre, introduced by Josepho, who successfully exploited the media, was a huge success. According to press reports, in half a year, a daily two thousand people, including the state governor, were photographed in the cabins. The huge sensation came when in March 1927, a consortium bought Josepho’s stake in Photomaton Inc. for $ 1 million. The news about the proverbial sum and the fabulous story of Josepho presenting him as a self-made man circulated in the global press and stimulated the photobooth’s rapid spread. By 1927, the company set up 95 machines in thirty cities in the United States.

Photomaton Inc. only owned the US and Russian patents (the latter was never used). The Photomaton’s rights for the rest of the world were sold by Josepho before March 1927. These rights were finally transferred in March 1928 to Clarence Hatry’s Photomaton Parent Corporation listed on the London Stock Exchange. Following several transactions, Hatry’s Corporation transferred the rights to an obscure network of newly established regional and national Photomaton companies. (Hatry’s parent company also became a major shareholder in American Photomaton Inc. in June 1928, with the purchase of one-third of the shares.)

In 1928, Josepho’s invention, the brand, and the network of companies behind it began expanding outside of the US. Photobooths turned up in London (February), Paris (June), Berlin (October), Vienna (November), and Budapest (December), where two machines operated in the “Corvin” department store. The invention soon reached many parts of the world, including the whole of Europe, as well as Turkey, Palestine, North Africa, Singapore, China, Australia, New Zealand, etc. Hatry’s financial downfall on September 17, 1929, which also resulted in his imprisonment, dragged not only the London Stock Exchange but also Photomaton companies around the world. While the multimillion-dollar Photomaton bubble burst, the machines continued to operate. Some saw the fun in them; others used to take their ID photos.

First column: Anna Cs. Horváth (Credit: Collection of János Mátyás Balogh); unknown Hungarian girls (Credit: Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár/National Archives of Hungary); unknown Hungarian man (Credit: Collection of János Mátyás Balogh)

Second column: unknown woman (Credit: Collection of Károly Kincses); unknown couple (Credit: Collection of Károly Kincses)

Third column: Erzsébet Helfer (wife of the Hungarian writer and poet Milán Füst) Credit: Petőfi Irodalmi Múzeum/Petőfi Literary Museum

The word “photomaton” became a common noun in several languages; in French and Spanish, ID photos are commonly referred to as “photomatons.” The images made in the booth were self-portraits taken in a standard, professional environment. While photographic instructions were absent, one can notice the adherence to certain norms and conventions.

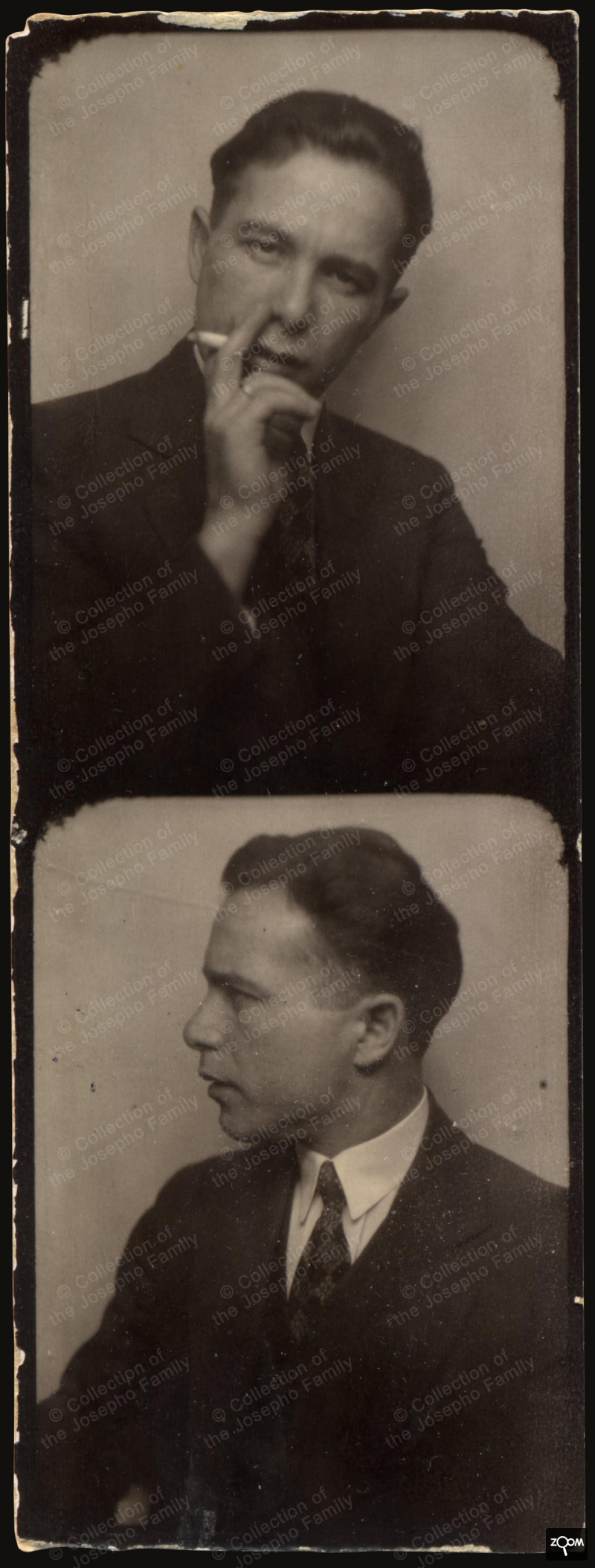

Anatol Josepho died on December 16, 1980, in La Jolla, California. The inventor of the Photomaton acquired significant wealth from the sale of his patents. He spent a large portion of it on charity, including donating land to a scout camp in California and supporting universities in Israel. However, his most enduring legacy was the hitherto unknown, more honest, natural and unique face of the world that was possible to learn and preserve through the snapshots taken in his photobooths.

Credit: Collection of the Josepho Family

This short essay is based on the following article of the author published earlier in Hungarian:

BALOGH János Mátyás: Stickyback és Photomaton: portréfotódivatok a 20. század első évtizedeiben. [‘Stickyback and Photomaton: Trends in Portrait Photography in the First Decades of the Twentieth Century.’] Korall [Hungarian Journal for Social History], 19. évf. 73. sz. (2018) p. 79–111.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Mátyás Mervay for his help and advice, Katalin Bognár, Csilla E. Csorba, Peter Eyckerman, Zsuzsa Farkas, Patrick Feaster, Miklós Grégász, Sharon Josepho, Károly Kincses, Ágota Lukács, Eduardo Martínez and Zita Nagy for the illustrations and Attila Nagy for the graphic solutions.

If you have any information or remark about the topic, please contact the author by e-mail

(enyveshat @ gmail . com).

Új hozzászólás

A hozzászóláshoz regisztráció és bejelentkezés szükséges